During our trip to the States we made it a priority to visit Cherith Brook Catholic Worker Community where Elisabeth and I met and lived for 4 years. During those 4 years we grew and learned a lot while practicing daily what it can look like to follow Jesus together in community. This time at Cherith Brook shaped us deeply and in many ways has led us to start to the Mustard Seed Community here in Luleå. Cherith Brook is a residential Christian community in Kansas City that practices the works mercy on a regular basis. One way they do this is by opening their home for breakfast, showers, and clean clothes for those on the streets in KC. Cherith Brook has five key principles which shape their life together and take visible form in a variety of ways. These principles are: nonviolence, hospitality, community, downward mobility and the revaluing of land and labor. In order to sustain their active life the members of Cherith Brook practice regular rhythms of prayer and Sabbath. During our visit, Elisabeth and I took the time to ask a few questions to Jodi Garbison, one of the founding members of Cherith Brook, as well as Butch, Nana and Lois who are each Elders at Cherith Brook.

During our trip to the States we made it a priority to visit Cherith Brook Catholic Worker Community where Elisabeth and I met and lived for 4 years. During those 4 years we grew and learned a lot while practicing daily what it can look like to follow Jesus together in community. This time at Cherith Brook shaped us deeply and in many ways has led us to start to the Mustard Seed Community here in Luleå. Cherith Brook is a residential Christian community in Kansas City that practices the works mercy on a regular basis. One way they do this is by opening their home for breakfast, showers, and clean clothes for those on the streets in KC. Cherith Brook has five key principles which shape their life together and take visible form in a variety of ways. These principles are: nonviolence, hospitality, community, downward mobility and the revaluing of land and labor. In order to sustain their active life the members of Cherith Brook practice regular rhythms of prayer and Sabbath. During our visit, Elisabeth and I took the time to ask a few questions to Jodi Garbison, one of the founding members of Cherith Brook, as well as Butch, Nana and Lois who are each Elders at Cherith Brook.

Josh: You put a lot of significance on practicing the Works of Mercy. Why is this so important for you and why do you put so much effort into this?

Jodi: I think we find the Works of Mercy central to our faith and our lives because our faith is one of action. I personally am inspired to live that faith when I embody it and not just talk about it, or read about it, or think about it, or hear sermons about it. I feel like I’m most connected with God when I am connected with others. When we started this community 13 years ago we had a certain quote in mind that goes something like this: “If you’ve come to help me then you’re wasting your time. But if you’ve come because you realize that your own liberation is bound up with mine then let’s work together.” This has shaped how and why we do things. It has brought our paths together which I think equals the playing field. It’s not like (after we have practiced the Works of Mercy) we can say, “Now you owe me” or “I’m doing good.”

Josh: Instead it’s more like we all benefit from the Works of Mercy. The rich our freed from the endless trap of gaining and maintaining more wealth and the poor are relieved from the weight and stress of not having enough to live on.

Jodi: Yeah, you could say that.

Josh: And isn’t that kind of what the Poor People’s Campaign is about?

Jodi: Yeah, I would say so. Although I would also say that one distinguishing thing about the Poor People’s Campaign is that it is not a movement of leaders that are trying to inspire poor people or to connect poor people to a movement. It’s more like a movement that’s being led from the bottom, from those who don’t have. So it requires those folks who have privilege or resources to follow, which is a good shift.

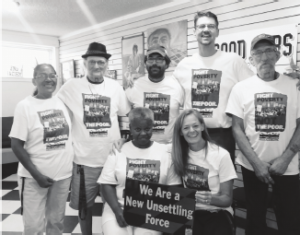

(“The Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival is uniting tens of thousands of people across the country to challenge the evils of systemic racism, poverty, the war economy, ecological devastation and the nation’s distorted morality.” Taken from poorpeoplescampaign.org. Many of the leaders of Cherith Brook are deeply engaged in the Poor Peoples Campaign and are organizing to get more people from the neighborhood involved.)

Josh: Butch, can you tell me about the Poor People’s Campaign and how you are involved?

Butch: I got involved because of some of the issues. Lots of things that are being slapped at the poor that aren’t necessarily the poor’s fault. Things that absolutely are not going to help them. For example, they made it a law that you have to have a vehicle in order to take scrap metal to the scrap yard. (This new law eliminates the possibility for many of Kansas City’s poor to make money by recycling metal at the scrap yard.) The lawmakers should instead be trying to help the poor by providing more jobs and creating affordable housing.

Josh: Why do you think they’re not doing that?

Butch: Gentrification. It’s a word. Look it up. It means the wealthy are creating a neighborhood the way they want it to be. They want the city to look a certain way for new people coming into it. This is an old neighborhood. A lot of poor people come here because the services are here. But now the rich want this area back and they are trying to do away with the poor people’s ability to live in this neighborhood.

Josh: But where do they want the poor to go?

Butch: They don’t care. You’re not allowed to be poor in America. If you are poor they call you lazy or addicted, or whatever. They just want to you stop being here. But you can’t very well just stop being here. The Poor People’s Campaign is still behind. We need to get ahead of the politics and the train of thought that these people have in office and start campaigning for a better life for the people who are poor. Nothing’s gonna change unless we do something about schooling, jobs and housing.

Josh: If you were to tell a rich person or a politician what they could do to help create change, what would you say to them?

Butch: Go out to the street and find a homeless person and take him home with you. Let him take a shower, change his clothes, and give him something to eat. It might not fix all his problems but it sure will make him feel better and you’ll learn a lot yourself. He’ll still be homeless unless he can find some way to make money. You see, when you cut out the possibilities for the poor to make money you only make them poorer so they don’t have any way to take care of themselves. That’s why there are so many homeless, because there ain’t no way to take care of yourself. Why don’t you put the jobs out there that people need? Put a bus line to the job. It’s something. I don’t have all the answers, but I know that some of the things they’re trying to do are just counterproductive.

Elisabeth: Nana, how did you get involved with the Poor People’s Campaign?

Nana: Through volunteering at Cherith Brook.

Elisabeth: What do you hope to achieve through your efforts?

Nana: In my lifetime I wanna see changes for my grandchildren and for their peers, and for everybody in the world that’s living under the poverty line or on the poverty line. But it’s like two steps forward and one step back. I get frustrated when people don’t show up, when they don’t want to work for change.

Elisabeth: Do you think that race has anything to do with poverty?

Nana: It’s not even a race issue. It’s a people issue.

Lois: It’s about all races and nationalities coming together to stop this poverty. I try not to be prejudice but sometimes when I think about what happened to my people I just get angry. When our people, the Native Americans and the Lakota Nation, which is my nation, tried to do what Martin Luther King Jr. did and stand up for our rights, we got slaughtered. But the Poor People’s Campaign is about everyone united and together and getting this done as one. And not just here but with all ethnicities around the world, uniting together and working for change.

Elisabeth: What kind of change do you hope to see through the Poor People’s Campaign?

Lois: I hope that the Poor People’s Campaign will open people’s eyes so they understand that we need to stop all this building for the rich and start building for people that actually need help. We need jobs and wages need to go up. I hope to see all of this militarism, poverty and crime just come to an end.

Josh: In this day and age of divisiveness, of hate and building walls to keep people out, do you really think that campaigning for moral revival and doing the Works of Mercy really matters?

Jodi: Right after Trump was elected, there were fifteen of us from Cherith Brook that went to the women’s march on Washington. We rented a van and drove the whole way there and back. We were on fire when we saw how many people came and it was so inspiring. But when we got back we felt really overwhelmed and discouraged not knowing how we were going to sustain our outrage for four years. And instead of feeling inspired we started to feel the other extreme of hopelessness and defeat. But we decided we couldn’t continue on in either of those extremes. We decided that what we can do in these four years is to continue to open our doors for welcome. What we can do for many years to come is to offer a radical hospitality, welcoming people into our home, feeding people and clothing people. What is the counter message to building walls? No walls. So that’s why we painted murals on the front of our house saying “Welcome” in 15 different languages and reminding folks that Jesus was also a refugee. After Trump was elected we knew that our response as well as the church’s response had to be clear and counter to what Trump was and is saying. Our response has to be loving. Our response should be “welcome”. Our response should be “Yes”. Trump or no Trump, this should be our response.

Jodi: Right after Trump was elected, there were fifteen of us from Cherith Brook that went to the women’s march on Washington. We rented a van and drove the whole way there and back. We were on fire when we saw how many people came and it was so inspiring. But when we got back we felt really overwhelmed and discouraged not knowing how we were going to sustain our outrage for four years. And instead of feeling inspired we started to feel the other extreme of hopelessness and defeat. But we decided we couldn’t continue on in either of those extremes. We decided that what we can do in these four years is to continue to open our doors for welcome. What we can do for many years to come is to offer a radical hospitality, welcoming people into our home, feeding people and clothing people. What is the counter message to building walls? No walls. So that’s why we painted murals on the front of our house saying “Welcome” in 15 different languages and reminding folks that Jesus was also a refugee. After Trump was elected we knew that our response as well as the church’s response had to be clear and counter to what Trump was and is saying. Our response has to be loving. Our response should be “welcome”. Our response should be “Yes”. Trump or no Trump, this should be our response.

So, yes it matters. Practicing the Works of Mercy matters. We can’t expect the state to do this work because that’s not the lens they see things through. We see things from a Christian perspective and that perspective tells us that we are responsible for our neighbor. That’s what sets us apart as Christians. We have a call to love our neighbor. The Works of Mercy matter as far as the ripple effect will extend. Like when you throw a pebble into a pond, it causes a ripple effect. What we do causes a ripple effect that causes change. And we hope that that ripple effect will extend outside of this place and beyond.